I got my copy of the Historical Novels Review today. It's a great publication for readers and writers of historical fiction, and in case you're new to this blog, I contribute some reviews to it. So without further ado, here are three of my reviews from the November 2006 issue: Mary by Janis Cooke Newman (about Mary Tood Lincoln), Gatsby's Girl by Caroline Preston (F. Scott Fitzgerald's old flame), and Loving Will Shakespeare by Carolyn Meyer (Anne Hathaway). I enjoyed each of them very much.

Mary: A Novel

Janis Cooke Newman

Committed to the Bellevue Place Sanitarium by her eldest son in 1875, Mary Todd Lincoln begins to write the story of her life in order to pass her sleepless nights and to keep herself sane—and also to gain the love of her cold-natured son. As Mary reflects upon her past, she also makes new acquaintances in the present, notably that of Minnie Judd, a fellow sanitarium inmate.

Minnie is starving herself in order to win the love of her indifferent husband, and Mary soon recognizes a kindred spirit in the young woman, for Mary’s life has also been an elusive quest for love, thwarted sometimes by death, sometimes by the frigidity of those whose affections she seeks to gain. Minnie’s quest, however, is doomed to defeat, while Mary’s ultimately ends in self-discovery.

Mary, however, is far more than just an account of a woman’s search for love. The novel is also a story of the Lincoln marriage, a mutually loving one marked in turn by defeat and triumph, by shared happiness and shared tragedy. Both Lincoln and Mary are vividly drawn characters, but Mary, as the center of the novel, is inevitably the more so. Her charm and wit are present throughout this book, but her faults—her temper, her extravagance, even on one occasion her infidelity—are amply on display. The novel is also, of course, one of a nation divided by civil war, and this gives rise to some memorable scenes, particularly a postwar visit to Richmond where the Lincolns get very different receptions from black Southerners and from white Southerners.

Moving and with an almost palpable compassion for its subject, yet clear-eyed and even humorous at times, this is a book I will be re-reading.

Gatsby’s Girl: A Novel

Caroline Preston

In 1915, F. Scott Fitzgerald met a society girl, Ginevra King, with whom he had a brief romance before she lost interest in him. Gatsby’s Girl, with a Ginevra Perry as the heroine, is loosely based on this episode in Fitzgerald’s life; the author, as she explains in a detailed, informative historical note, has purposely altered characters and events.

Dazzled by a handsome aviator-in-training at a party, fickle Ginevra wastes no time in ridding herself of Fitzgerald, a “silly college boy” with a pronounced taste for highballs who “’writes,’ plays dress-up, and is flunking geometry.” Five years later, Ginevra, married and a mother, realizes that her spurned suitor has become famous and that a female character in his new novel bears a distinct resemblance to herself. From that point on, Ginevra’s and Fitzgerald’s lives will occasionally intersect and parallel each other, with sometimes surprising results.

With Fitzgerald and Ginevra’s romance over, I wondered at first whether Ginevra, the narrator, was going to be able to carry the rest of Gatsby’s Girl by herself. I needn’t have worried, however, for Ginevra turns out to be more than simply a shallow debutante. As she faces an unhappy marriage, a mentally ill child, and the consequences of her own recklessness with increasing maturity, sensitivity, and self-awareness, she gains the reader’s respect. Gatsby’s Girl is an engaging and absorbing novel in which the heroine proves wrong her old boyfriend’s declaration, “There are no second acts in American lives.”

Loving Will Shakespeare

Carolyn Meyer

Just before the plague returns to England, seven-year-old Agnes (Anne) Hathaway and her family are invited to a christening by friends: John and Mary Shakespeare, who have just had a son, William. From that point on, Anne’s and Will’s lives will constantly intersect, even when the pair are miles apart.

Despite the title, this appealing novel is not so much the story of Anne and Will’s courtship and marriage as it is of Anne’s coming of age, though the budding playwright is never very far offstage and the love story does assume prominence in the latter part of the book. Growing up as a yeoman farmer’s daughter, Anne, the narrator, is an ordinary girl but by no means a dull one. She must cope with her difficult stepmother and half-sister, the temptations posed by men, the deaths of loved ones, worries over friends who choose to practice Catholicism, and her increasing fear of spinsterhood, and she does so with resourcefulness and good humor. All of this plays out against the vividly rendered backdrop of life in Elizabethan England: the once-in-a-lifetime excitement of a royal progress, the annual May Day and Yuletide feasts, the periodic visitations of plague and sweating sickness, the daily business of running a farm. These elements make this an engrossing story, one that should appeal to adults as well as to the teens for whom it is intended. Ages 12 and up.

Medieval History, and Tudors Too!

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

A Medieval Love Story: Joan of Acre and Ralph de Monthermer

We had a dark post last week, so here's a switch: a medieval love story with a happy ending.

One of the more unlikely romances in the late thirteenth century was that between Joan of Acre, daughter of King Edward I, and Ralph de Monthermer, son of the Lord Knows Who. For Ralph, a squire in Joan's household, was of such obscure origins that his parentage is unknown.

Joan of Acre was born in 1272 in Acre, or Akko, in what is now Israel. Her parents, Eleanor of Castile and the future Edward I, had gone there on crusade. Joan was soon sent to her maternal grandmother in Castile, where she remained until 1278. Her father, now King of England, had plans to marry her to Hartman, son of the King of the Romans, but the young man died in a shipwreck in 1282 before the couple could marry. Undaunted, Edward I soon began searching around for another suitable husband. Soon he lit on one: Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester. Gilbert de Clare, probably the most powerful baron in England at the time and one whose relations with the king had long been stormy. Gilbert had the disadvantage of already having a wife, Alice de Lusignan, but the couple had long been estranged, and in 1285, the marriage was annulled. In 1290, after drawn-out negotiations and the obtaining of a papal dispensation, eighteen-year-old Joan was finally married to forty-six-year-old Gilbert. Before Gilbert's death in December 1295, the couple efficiently produced four children: Gilbert, Eleanor, Margaret, and Elizabeth.

Joan has taken hard knocks at the hands of both historians and novelists. Mary Anne Everett Green in her Lives of the Princesses of England characterizes her as a neglectful mother and a "giddy princess," and other Victorian-era historians, along with many novelists, have acquiesced in this judgment. There seems to be little evidence to support this with regard to her motherhood; though Edward I did arrange for Joan's son Gilbert to live at court when he was seven, this was hardly an atypical arrangement for a noble boy who was also the king's grandson. As for Joan's giddiness, Michael Altschul has commented on the "marked ability" with which Joan controlled the Clare lands after Gilbert's death. There is certainly no evidence that supports the picture of Joan that is painted by romance novelist Virginia Henley, who depicts her as a promiscuous young woman ready to jump into bed with any willing knight.

What can be said about Joan, however, was that she had spirit and willfulness. During her parents' absence in Gascony, when Joan was in her early teens, she became involved in a dispute with the treasurer of her household and refused to accept money from him; her father had to pay her debts when he returned to England. After her marriage, she left court to be alone with her new husband at his manors, to the displeasure of her father, who in reprisal seized seven robes that had been made for her. When her younger brother, the future Edward II, became estranged from Edward I, Joan offered to lend him her seal.

Among the squires in Gilbert de Clare's vast household was one Ralph de Monthermer. Nothing is known of his background, but he soon caught the eye of his widowed mistress, who sent him to her father to be knighted. Sometime at the beginning of 1297, the couple were secretly married.

Edward I, cheerfully ignorant of this match, had meanwhile been searching around for another husband for his daughter, and it is safe to say that Monthermer was not one of the candidates. His words when he heard the rumors about his daughter's attraction to her squire are unrecorded, and in any case are probably best left to the imagination. He seized Joan's estates and formally announced his daughter's betrothal to the Count of Savoy in March 1297. Joan, however, had become "conscious that she was in a situation which would render the disclosure of her marriage inevitable," as Green delicately puts it, and she apparently broke the news of the marriage to her father, who promptly clapped Monthermer into prison at Bristol Castle.

Either before informing her father of her marriage, or after Monthermer had been put into prison--the accounts vary--Joan sent her little daughters to visit their grandfather the king in hopes that they would soften his mood. Evidently, though, more was needed than just the youthful antics of the three Clare sisters. After a great deal of discussion at court about the matter, Joan, as the chronicles report, was at last allowed to plead for herself before her father, at which time she is said to have told the king that as it was no disgrace for an earl to marry a poor woman, it was not blameworthy for a countess to advance a capable young man. This defense is said to have pleased Edward I, though it is probable that Joan's pregnancy, which would have been visible at the time of this exchange in July 1297, also convinced the king to accept the situation. He restored most of Joan's lands to her and pardoned Monthermer, who from November 1297 onward was referred to as the Earl of Gloucester. In the meantime, the couple's first child, named Mary, had been born. She was followed by three others: Thomas, Edward, and Joan.

Ralph soon found himself busy fighting Scots for his new father-in-law, which brought him quickly into favor with the king. In 1301, Edward I restored Tonbridge and Portland to Ralph and Joan in consideration of Ralph's good services in Scotland. Ralph also was on cordial terms with young Prince Edward, who frequently wrote to him. Joan too was friendly with her much younger brother Edward, even offering him her seal when Edward was estranged from his father.

On April 23, 1307, Joan of Acre died. Some Internet sources claim that she died in childbirth--unfortunately, hardly an implausible scenario--but none that I have seen mention a source for this information. Neither Green, Altschul, nor Frances Underwood specify a cause for her death. She was only thirty-five. Ralph was probably not present, being engaged in Scotland at the time. Joan was buried at the priory of Clare in Suffolk. According to Underwood, Osbern Bokenham, a friar there, relayed the odd story that in 1359, Elizabeth de Burgh, Joan's last surviving Clare daughter, inspected her mother's body and found the corpse to be intact. Bokenham also reported that miracles were said to occur at Joan's tomb, including the healing of toothache, back pain, and fever.

Edward I, who ordered that masses be said for his daughter, was himself in poor health; he died in July 1307. Having been styled an earl in right of his wife, Ralph lost his title shortly after her death; Joan and Gilbert de Clare's son, another Gilbert, became the next Earl of Gloucester. The new king, Edward II, granted Ralph five thousand marks for his surrender of the Clare lands to Gilbert, then still a minor. Though his importance had been much diminished, he remained active in Edward II's reign, holding positions such as keeper of the forest south of Trent, and seems to have been neutral or on the king's side during the latter's disputes with his barons. In 1314, he was taken prisoner at Bannockburn but was treated as an honored guest by Robert Bruce, who allowed him to return to England without having to pay a ransom. A story goes that years before, Monthermer, having gotten wind of a plan of Edward I to capture Bruce while he was in London, had sent him coins bearing the king's head and a pair of spurs as a hint that he should slip away. Bruce, having profited from the hint, later remembered this good deed when Monthermer became his prisoner.

Around November 1318, Monthermer made another runaway match, this time to Isabel de Hastings, a widow. Whatever motivated the match, it was an opportune one for Ralph, for Isabel was a member of the Despenser family. Her father, Hugh le Despenser the elder, had long been loyal to Edward II; her brother, Hugh le Despenser the younger, was rapidly becoming Edward II's most trusted advisor (and possibly, his lover). Monthermer, a contemporary of the elder Despenser, was probably at least twenty years older than his new bride. Because the couple had married without the king's license, Isabel's dower lands were seized, but the couple were pardoned the next year in exchange for paying a fine of a thousand marks, which was remitted in 1321.

In 1324, Edward II showed his displeasure with his queen, Isabella, by reducing her household. Among the changes made were that the royal daughters, Eleanor and Joan, were put into Ralph and Isabel's care. Although the timing suggests that Edward II was motivated in part by hostility toward Queen Isabella, it was also typical to give royal children households of their own. The girls and their new guardians stayed at Marlborough Castle.

Ralph died on April 5, 1325, aged sixty-three, and was buried in the Grey Friars' church at Salisbury. The timing of his death was also opportune: it spared him from having to choose whether to remain loyal to Edward II or to support Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer, who overthrew the king in 1326. Ralph's connection with the Despenser family might have been a fatal one had he elected to side with the king. The king and queen's daughters remained with the widowed Isabel until October 1326, when Queen Isabella was reunited with them at Bristol Castle, where they and Hugh le Despenser the elder were staying. Isabel was presumably at the castle with her charges and may have had the misfortune of seeing her father's surrender to Isabella and Mortimer and his execution the following day. Her brother was executed less than a month later.

Isabel herself does not seem to have been punished by the new rulers, although in June 1328, she acknowledged a debt of nearly three hundred pounds to Queen Isabella. Whether this was a real debt stemming out of her care of the queen's children or whether she was forced to make the acknowledgment to avoid the wrath of the queen's regime is unknown.

Ralph and Isabel had apparently had no surviving children. Ralph's two sons by Joan of Acre, Thomas and Edward, were on good enough terms with the new regime to be knighted in 1327, but Thomas later joined Henry, Earl of Lancaster's rebellion against Queen Isabella and Mortimer, while Edward became entangled with the Earl of Kent, Edward II's half-brother, who had plotted to release Edward II, whom he believed to be still alive, from captivity. The earl, who had likely been entrapped into the plot by Queen Isabella and Mortimer, was beheaded in 1330 for his fraternal loyalty, but Edward de Monthermer got off more lightly, being imprisoned in Winchester Castle at the crown's expense. Fortunately for Edward, Mortimer's days were numbered; he was seized by Edward III in October 1330 and hanged the following month. Edward de Monthermer's lands were restored to him in December 1330. Thomas, who had been fined for his role in Lancaster's rebellion, had his fine remitted in January 1331.

Edward de Monthermer, who had taken part in Edward III's wars but who had fallen ill, came to live with his half-sister Elizabeth de Burgh in 1339 and died before February 1340. He was buried near Joan of Acre; Elizabeth de Burgh, who took charge of his funeral, had his tomb made. Ralph and Joan's younger daughter, Joan, became a nun at Amesbury; their older daughter, Mary, wed the Earl of Fife. Thomas de Monthermer married Margaret, the widow of Henry Teyes, and died in 1340 at the sea battle of Sluys. His daughter, Margaret, married John de Montacute, the younger son of William de Montacute, Earl of Salisbury. John and Margaret's son, John, later succeeded to the earldom of Salisbury. From him would descend Warwick the Kingmaker and his daughter Anne, queen to Richard III. It was an impressive lineage for Ralph de Monthermer, the obscure squire who had married a princess.

One of the more unlikely romances in the late thirteenth century was that between Joan of Acre, daughter of King Edward I, and Ralph de Monthermer, son of the Lord Knows Who. For Ralph, a squire in Joan's household, was of such obscure origins that his parentage is unknown.

Joan of Acre was born in 1272 in Acre, or Akko, in what is now Israel. Her parents, Eleanor of Castile and the future Edward I, had gone there on crusade. Joan was soon sent to her maternal grandmother in Castile, where she remained until 1278. Her father, now King of England, had plans to marry her to Hartman, son of the King of the Romans, but the young man died in a shipwreck in 1282 before the couple could marry. Undaunted, Edward I soon began searching around for another suitable husband. Soon he lit on one: Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester. Gilbert de Clare, probably the most powerful baron in England at the time and one whose relations with the king had long been stormy. Gilbert had the disadvantage of already having a wife, Alice de Lusignan, but the couple had long been estranged, and in 1285, the marriage was annulled. In 1290, after drawn-out negotiations and the obtaining of a papal dispensation, eighteen-year-old Joan was finally married to forty-six-year-old Gilbert. Before Gilbert's death in December 1295, the couple efficiently produced four children: Gilbert, Eleanor, Margaret, and Elizabeth.

Joan has taken hard knocks at the hands of both historians and novelists. Mary Anne Everett Green in her Lives of the Princesses of England characterizes her as a neglectful mother and a "giddy princess," and other Victorian-era historians, along with many novelists, have acquiesced in this judgment. There seems to be little evidence to support this with regard to her motherhood; though Edward I did arrange for Joan's son Gilbert to live at court when he was seven, this was hardly an atypical arrangement for a noble boy who was also the king's grandson. As for Joan's giddiness, Michael Altschul has commented on the "marked ability" with which Joan controlled the Clare lands after Gilbert's death. There is certainly no evidence that supports the picture of Joan that is painted by romance novelist Virginia Henley, who depicts her as a promiscuous young woman ready to jump into bed with any willing knight.

What can be said about Joan, however, was that she had spirit and willfulness. During her parents' absence in Gascony, when Joan was in her early teens, she became involved in a dispute with the treasurer of her household and refused to accept money from him; her father had to pay her debts when he returned to England. After her marriage, she left court to be alone with her new husband at his manors, to the displeasure of her father, who in reprisal seized seven robes that had been made for her. When her younger brother, the future Edward II, became estranged from Edward I, Joan offered to lend him her seal.

Among the squires in Gilbert de Clare's vast household was one Ralph de Monthermer. Nothing is known of his background, but he soon caught the eye of his widowed mistress, who sent him to her father to be knighted. Sometime at the beginning of 1297, the couple were secretly married.

Edward I, cheerfully ignorant of this match, had meanwhile been searching around for another husband for his daughter, and it is safe to say that Monthermer was not one of the candidates. His words when he heard the rumors about his daughter's attraction to her squire are unrecorded, and in any case are probably best left to the imagination. He seized Joan's estates and formally announced his daughter's betrothal to the Count of Savoy in March 1297. Joan, however, had become "conscious that she was in a situation which would render the disclosure of her marriage inevitable," as Green delicately puts it, and she apparently broke the news of the marriage to her father, who promptly clapped Monthermer into prison at Bristol Castle.

Either before informing her father of her marriage, or after Monthermer had been put into prison--the accounts vary--Joan sent her little daughters to visit their grandfather the king in hopes that they would soften his mood. Evidently, though, more was needed than just the youthful antics of the three Clare sisters. After a great deal of discussion at court about the matter, Joan, as the chronicles report, was at last allowed to plead for herself before her father, at which time she is said to have told the king that as it was no disgrace for an earl to marry a poor woman, it was not blameworthy for a countess to advance a capable young man. This defense is said to have pleased Edward I, though it is probable that Joan's pregnancy, which would have been visible at the time of this exchange in July 1297, also convinced the king to accept the situation. He restored most of Joan's lands to her and pardoned Monthermer, who from November 1297 onward was referred to as the Earl of Gloucester. In the meantime, the couple's first child, named Mary, had been born. She was followed by three others: Thomas, Edward, and Joan.

Ralph soon found himself busy fighting Scots for his new father-in-law, which brought him quickly into favor with the king. In 1301, Edward I restored Tonbridge and Portland to Ralph and Joan in consideration of Ralph's good services in Scotland. Ralph also was on cordial terms with young Prince Edward, who frequently wrote to him. Joan too was friendly with her much younger brother Edward, even offering him her seal when Edward was estranged from his father.

On April 23, 1307, Joan of Acre died. Some Internet sources claim that she died in childbirth--unfortunately, hardly an implausible scenario--but none that I have seen mention a source for this information. Neither Green, Altschul, nor Frances Underwood specify a cause for her death. She was only thirty-five. Ralph was probably not present, being engaged in Scotland at the time. Joan was buried at the priory of Clare in Suffolk. According to Underwood, Osbern Bokenham, a friar there, relayed the odd story that in 1359, Elizabeth de Burgh, Joan's last surviving Clare daughter, inspected her mother's body and found the corpse to be intact. Bokenham also reported that miracles were said to occur at Joan's tomb, including the healing of toothache, back pain, and fever.

Edward I, who ordered that masses be said for his daughter, was himself in poor health; he died in July 1307. Having been styled an earl in right of his wife, Ralph lost his title shortly after her death; Joan and Gilbert de Clare's son, another Gilbert, became the next Earl of Gloucester. The new king, Edward II, granted Ralph five thousand marks for his surrender of the Clare lands to Gilbert, then still a minor. Though his importance had been much diminished, he remained active in Edward II's reign, holding positions such as keeper of the forest south of Trent, and seems to have been neutral or on the king's side during the latter's disputes with his barons. In 1314, he was taken prisoner at Bannockburn but was treated as an honored guest by Robert Bruce, who allowed him to return to England without having to pay a ransom. A story goes that years before, Monthermer, having gotten wind of a plan of Edward I to capture Bruce while he was in London, had sent him coins bearing the king's head and a pair of spurs as a hint that he should slip away. Bruce, having profited from the hint, later remembered this good deed when Monthermer became his prisoner.

Around November 1318, Monthermer made another runaway match, this time to Isabel de Hastings, a widow. Whatever motivated the match, it was an opportune one for Ralph, for Isabel was a member of the Despenser family. Her father, Hugh le Despenser the elder, had long been loyal to Edward II; her brother, Hugh le Despenser the younger, was rapidly becoming Edward II's most trusted advisor (and possibly, his lover). Monthermer, a contemporary of the elder Despenser, was probably at least twenty years older than his new bride. Because the couple had married without the king's license, Isabel's dower lands were seized, but the couple were pardoned the next year in exchange for paying a fine of a thousand marks, which was remitted in 1321.

In 1324, Edward II showed his displeasure with his queen, Isabella, by reducing her household. Among the changes made were that the royal daughters, Eleanor and Joan, were put into Ralph and Isabel's care. Although the timing suggests that Edward II was motivated in part by hostility toward Queen Isabella, it was also typical to give royal children households of their own. The girls and their new guardians stayed at Marlborough Castle.

Ralph died on April 5, 1325, aged sixty-three, and was buried in the Grey Friars' church at Salisbury. The timing of his death was also opportune: it spared him from having to choose whether to remain loyal to Edward II or to support Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer, who overthrew the king in 1326. Ralph's connection with the Despenser family might have been a fatal one had he elected to side with the king. The king and queen's daughters remained with the widowed Isabel until October 1326, when Queen Isabella was reunited with them at Bristol Castle, where they and Hugh le Despenser the elder were staying. Isabel was presumably at the castle with her charges and may have had the misfortune of seeing her father's surrender to Isabella and Mortimer and his execution the following day. Her brother was executed less than a month later.

Isabel herself does not seem to have been punished by the new rulers, although in June 1328, she acknowledged a debt of nearly three hundred pounds to Queen Isabella. Whether this was a real debt stemming out of her care of the queen's children or whether she was forced to make the acknowledgment to avoid the wrath of the queen's regime is unknown.

Ralph and Isabel had apparently had no surviving children. Ralph's two sons by Joan of Acre, Thomas and Edward, were on good enough terms with the new regime to be knighted in 1327, but Thomas later joined Henry, Earl of Lancaster's rebellion against Queen Isabella and Mortimer, while Edward became entangled with the Earl of Kent, Edward II's half-brother, who had plotted to release Edward II, whom he believed to be still alive, from captivity. The earl, who had likely been entrapped into the plot by Queen Isabella and Mortimer, was beheaded in 1330 for his fraternal loyalty, but Edward de Monthermer got off more lightly, being imprisoned in Winchester Castle at the crown's expense. Fortunately for Edward, Mortimer's days were numbered; he was seized by Edward III in October 1330 and hanged the following month. Edward de Monthermer's lands were restored to him in December 1330. Thomas, who had been fined for his role in Lancaster's rebellion, had his fine remitted in January 1331.

Edward de Monthermer, who had taken part in Edward III's wars but who had fallen ill, came to live with his half-sister Elizabeth de Burgh in 1339 and died before February 1340. He was buried near Joan of Acre; Elizabeth de Burgh, who took charge of his funeral, had his tomb made. Ralph and Joan's younger daughter, Joan, became a nun at Amesbury; their older daughter, Mary, wed the Earl of Fife. Thomas de Monthermer married Margaret, the widow of Henry Teyes, and died in 1340 at the sea battle of Sluys. His daughter, Margaret, married John de Montacute, the younger son of William de Montacute, Earl of Salisbury. John and Margaret's son, John, later succeeded to the earldom of Salisbury. From him would descend Warwick the Kingmaker and his daughter Anne, queen to Richard III. It was an impressive lineage for Ralph de Monthermer, the obscure squire who had married a princess.

Friday, November 24, 2006

680 Years Ago Today in Hereford

Today is the 680th anniversary of the death of Hugh le Despenser the younger. I'm too lazy to write a proper blog entry about it. Instead, here's the scene as I wrote it in The Traitor's Wife. (It's not dinnertime fare.)

Leybourne and Stanegrave and their men had made Hugh’s journey to Hereford as miserable as Isabella and Mortimer could have wished. Lest any dozing village miss the fine sight of Hugh le Despenser chained to a mangy horse, a drummer and a trumpeter had been put at the head of the procession to announce his arrival well in advance. This was the cue for villagers to throw anything they could find at Hugh, and at Simon de Reading as well. Hardly anyone knew who the latter was, of course, but as he too was in chains, everyone realized that he had to be associated with Hugh, and his presence made the proceedings twice as fun and provided some consolation for those whose aim was too unsure to hit Hugh himself.

But the true festivities started when the troops, trailed by an ever-increasing crowd of citizens eager to see Hugh hang, reached the outskirts of Hereford, where they were met by a contingent of the queen’s men coming from the city, led by Jean de Hainault and Thomas Wake. There, to the delight of the crowd, Hugh and Simon were dragged off their horses and stripped naked, then redressed in tunics bearing their coats of arms reversed. With the help of a clerk, whose Latin was needed for the purpose, the words from the Magnificat “He has put down the mighty from their seat and hath exalted the humble” were etched into Hugh’s bare shoulders. His chest bore psalm verses beginning, “Why dost thou glory in malice, thou that art mighty in iniquity?” Thus decorated, and wearing a crown of nettles, he was put back on his horse. Then, to the blare of trumpets and drums, accompanied by the howling of the spectators, he was led into the city with Simon de Reading forced to march in front of him bearing his standard reversed. As there were only so many horse droppings that could be found to throw at the captives, the enterprising were selling eggs for that purpose.

Zouche had hoped to miss these proceedings. He had retrieved the records, and the little treasure that could be found, from Swansea, and had delivered his load to the queen two days before. But having made good time to Hereford, he could not leave once the execution had been scheduled. Thus, he was standing in the market square, near the queen, Mortimer, and the Duke of Aquitaine [the future Edward III], when Hugh and Simon, so covered in filth that they resembled scarecrows more than men, were brought there for trial.

Isabella, still clad in widow’s weeds, wore a look of resignation as William Trussell stepped forth to read the charges against Hugh. Only Mortimer, making no attempt to hide his own satisfaction, saw the sparkle in her eyes.

***

At what passed for his trial, Hugh’s mind wandered from the past to the present, sometimes lucidly, sometimes not. There were many charges against him, some true enough, some with a bit of truth to them, some so patently absurd that it was a wonder Trussell could keep a straight face. Piracy. Returning to England after his banishment. Procuring the death of the saintly Lancaster after imprisoning him on false charges. Executing other men who had fought against the king at Boroughbridge on false charges. Forcing the king to fight the Scots. Abandoning the queen at Tynemouth. (That again, Hugh thought.) Making war on the Christian Church. Disinheriting the king by inducing him to grant the earldom of Winchester to his father and the earldom of Carlisle to Harclay. Bribing persons in France to murder the queen and her son… He drifted off into a world where his death was not imminent, and when he was shaken back to the here and now once more, Trussell was still going on, perhaps beginning to bore those assembled a little. Trussell himself must have sensed this, for he sped through the last few charges (leading the king out of his realm to his dishonor and taking with him the treasure of the kingdom and the Great Seal) before he slowed his voice dramatically for what all were anticipating: his sentence. Though no one could have possibly been surprised by it, least of all Hugh himself, there were nonetheless appreciative gasps as Trussell, all but smacking his lips, informed Hugh what was to be done with him.

“Hugh, you have been judged a traitor since you have threatened all the good people of the realm, great and small, rich and poor, and by common assent you are also a thief. As a thief you will hang, and as a traitor you will be drawn and quartered, and your quarters will be sent throughout the realm. And because you prevailed upon our lord the king, and by common assent you returned to the court without warrant, you will be beheaded. And because you were always disloyal and procured discord between our lord the king and our very honorable lady the queen, and between other people of the realm, you will be disemboweled, and then your entrails will be burnt. Go to meet your fate, traitor, tyrant, renegade. Go to receive your own justice, traitor, evil man, criminal!”

***

At Hereford Castle, to which Hugh was dragged by four horses, a gallows fifty feet high had been erected. “Just for you!” said one of the men who untied him from his hurdle and hauled him toward the gallows. “Ain’t we the special one, now?”

Simon de Reading, having been drawn behind the usual two horses, was hung on a smaller gallows. Hugh, propped up between his guards because one of his ankles would not allow him to bear any weight on it, shakily crossed himself and whispered a prayer for Simon’s soul.

When he was twelve he had had to have a tooth drawn. His father, always anxious for him, had told him as he lay miserably in the barber’s chair, “Get a pleasant picture in your mind, son, and fix it there. It’ll take your mind off it as it happens.” He’d obeyed, fixing first on his new horse, then, more satisfyingly, on a buxom village maiden he’d long admired, and it had worked, at least to the extent that it’d taken his mind off his tooth until the barber actually yanked it. Eleanor, after the birth of their first son, had told him that her midwife had given her similar advice when her labor pains became intense. “She said, ‘Think of something you enjoy doing, and imagine yourself doing it,’ so I thought of making love to you. Isn’t that terrible? But it helped.”

He thought of his wedding night. He was nineteen years old and pulling the sheets off his skittish little bride, chosen for him by the great King Edward himself, and he had been the happiest creature in the world. She was lovely and sweet and all his, and it had not yet occurred to him to want anything more.

He’d been guilty of no greater sin back then than poaching the occasional deer, and if he had died at that time, there would have been no cheering. Perhaps someone might have even wept for him. If he’d just taken life as it came to him his old father would be nodding off in a comfortable chair by a roaring fire now and his wife would be welcoming some pretty heiress as their son Hugh’s new bride. His son Edward would be mooning over some wench and the rest of his children would be playing some absurd game. The king would be on his throne, taking the purely disinterested advice that Hugh could have offered him but never did.

He’d truly loved them all, and he’d brought them all to ruin. It was by far his worst sin. Why had not Trussell included that in his thunderings?

He prayed for forgiveness, perhaps audibly enough to be overheard by those surrounding him, for there was scornful laughter. Then a man in black appeared beside him. Of the faces that surrounded him, his was the only one that showed no hatred on it. It showed nothing, in fact; the man was simply following his trade. Hugh hoped he was reasonably good at it; Arundel’s executioner, as the queen’s men had delighted in informing him, had been a rank amateur who had taken twenty strokes to sever the earl’s head. He slid his rings off his fingers and handed them to his executioner. “Go to it,” he said tonelessly.

***

To separate them from the increasingly boisterous crowd, a little stand had been erected near the gallows for the queen and her son and the higher nobility. Still wearing a look of patient, slightly pained endurance, Isabella watched as Despenser, wearing nothing but his crown of nettles, was lifted aloft. Zouche, standing a few feet off with the queen’s other leaders, glanced at young Edward’s face but could read nothing in it.

After dangling in the air a short time, Hugh was lowered to a platform below the gallows, next to which a good-sized fire had been lit. For a moment, he lay still, much to the crowd’s dismay; then, after a few slaps from the executioner, he started to cough and gasp and opened his eyes. The executioner, satisfied that his charge was as awake as he was going to get, nodded to a boy who like a surgeon’s apprentice was standing nearby with several knives and an ax. The boy handed over the smallest of the knives, and the executioner bent to his work.

Despenser let out a strangled cry, and the executioner held up Hugh’s genitals. Amid the cheers and jests, Isabella’s smile was too slight to be detected as they quivered in the air. After dropping them in the fire (“Listen to ’em sizzle!” a spectator shouted happily. “Like bacon!”), the executioner took a larger knife and opened Hugh’s abdomen. Hugh moaned and turned his head back and forth, then grew quiet. He was motionless when his heart was plucked out and thrown into the fire.

The boy handed over the ax. “Behold the head of a traitor!”

The crowd shrieked with sheer joy, and men clapped each other on the backs and shoulders as if they had personally caught the king’s chamberlain and brought him to justice. As the head, which was to be sent to London, was carefully put aside, Zouche found that he could not watch Hugh’s blood-covered body being cut into four pieces. Instead, he stared at the ring on his right hand as he twirled it round and round.

Leybourne and Stanegrave and their men had made Hugh’s journey to Hereford as miserable as Isabella and Mortimer could have wished. Lest any dozing village miss the fine sight of Hugh le Despenser chained to a mangy horse, a drummer and a trumpeter had been put at the head of the procession to announce his arrival well in advance. This was the cue for villagers to throw anything they could find at Hugh, and at Simon de Reading as well. Hardly anyone knew who the latter was, of course, but as he too was in chains, everyone realized that he had to be associated with Hugh, and his presence made the proceedings twice as fun and provided some consolation for those whose aim was too unsure to hit Hugh himself.

But the true festivities started when the troops, trailed by an ever-increasing crowd of citizens eager to see Hugh hang, reached the outskirts of Hereford, where they were met by a contingent of the queen’s men coming from the city, led by Jean de Hainault and Thomas Wake. There, to the delight of the crowd, Hugh and Simon were dragged off their horses and stripped naked, then redressed in tunics bearing their coats of arms reversed. With the help of a clerk, whose Latin was needed for the purpose, the words from the Magnificat “He has put down the mighty from their seat and hath exalted the humble” were etched into Hugh’s bare shoulders. His chest bore psalm verses beginning, “Why dost thou glory in malice, thou that art mighty in iniquity?” Thus decorated, and wearing a crown of nettles, he was put back on his horse. Then, to the blare of trumpets and drums, accompanied by the howling of the spectators, he was led into the city with Simon de Reading forced to march in front of him bearing his standard reversed. As there were only so many horse droppings that could be found to throw at the captives, the enterprising were selling eggs for that purpose.

Zouche had hoped to miss these proceedings. He had retrieved the records, and the little treasure that could be found, from Swansea, and had delivered his load to the queen two days before. But having made good time to Hereford, he could not leave once the execution had been scheduled. Thus, he was standing in the market square, near the queen, Mortimer, and the Duke of Aquitaine [the future Edward III], when Hugh and Simon, so covered in filth that they resembled scarecrows more than men, were brought there for trial.

Isabella, still clad in widow’s weeds, wore a look of resignation as William Trussell stepped forth to read the charges against Hugh. Only Mortimer, making no attempt to hide his own satisfaction, saw the sparkle in her eyes.

***

At what passed for his trial, Hugh’s mind wandered from the past to the present, sometimes lucidly, sometimes not. There were many charges against him, some true enough, some with a bit of truth to them, some so patently absurd that it was a wonder Trussell could keep a straight face. Piracy. Returning to England after his banishment. Procuring the death of the saintly Lancaster after imprisoning him on false charges. Executing other men who had fought against the king at Boroughbridge on false charges. Forcing the king to fight the Scots. Abandoning the queen at Tynemouth. (That again, Hugh thought.) Making war on the Christian Church. Disinheriting the king by inducing him to grant the earldom of Winchester to his father and the earldom of Carlisle to Harclay. Bribing persons in France to murder the queen and her son… He drifted off into a world where his death was not imminent, and when he was shaken back to the here and now once more, Trussell was still going on, perhaps beginning to bore those assembled a little. Trussell himself must have sensed this, for he sped through the last few charges (leading the king out of his realm to his dishonor and taking with him the treasure of the kingdom and the Great Seal) before he slowed his voice dramatically for what all were anticipating: his sentence. Though no one could have possibly been surprised by it, least of all Hugh himself, there were nonetheless appreciative gasps as Trussell, all but smacking his lips, informed Hugh what was to be done with him.

“Hugh, you have been judged a traitor since you have threatened all the good people of the realm, great and small, rich and poor, and by common assent you are also a thief. As a thief you will hang, and as a traitor you will be drawn and quartered, and your quarters will be sent throughout the realm. And because you prevailed upon our lord the king, and by common assent you returned to the court without warrant, you will be beheaded. And because you were always disloyal and procured discord between our lord the king and our very honorable lady the queen, and between other people of the realm, you will be disemboweled, and then your entrails will be burnt. Go to meet your fate, traitor, tyrant, renegade. Go to receive your own justice, traitor, evil man, criminal!”

***

At Hereford Castle, to which Hugh was dragged by four horses, a gallows fifty feet high had been erected. “Just for you!” said one of the men who untied him from his hurdle and hauled him toward the gallows. “Ain’t we the special one, now?”

Simon de Reading, having been drawn behind the usual two horses, was hung on a smaller gallows. Hugh, propped up between his guards because one of his ankles would not allow him to bear any weight on it, shakily crossed himself and whispered a prayer for Simon’s soul.

When he was twelve he had had to have a tooth drawn. His father, always anxious for him, had told him as he lay miserably in the barber’s chair, “Get a pleasant picture in your mind, son, and fix it there. It’ll take your mind off it as it happens.” He’d obeyed, fixing first on his new horse, then, more satisfyingly, on a buxom village maiden he’d long admired, and it had worked, at least to the extent that it’d taken his mind off his tooth until the barber actually yanked it. Eleanor, after the birth of their first son, had told him that her midwife had given her similar advice when her labor pains became intense. “She said, ‘Think of something you enjoy doing, and imagine yourself doing it,’ so I thought of making love to you. Isn’t that terrible? But it helped.”

He thought of his wedding night. He was nineteen years old and pulling the sheets off his skittish little bride, chosen for him by the great King Edward himself, and he had been the happiest creature in the world. She was lovely and sweet and all his, and it had not yet occurred to him to want anything more.

He’d been guilty of no greater sin back then than poaching the occasional deer, and if he had died at that time, there would have been no cheering. Perhaps someone might have even wept for him. If he’d just taken life as it came to him his old father would be nodding off in a comfortable chair by a roaring fire now and his wife would be welcoming some pretty heiress as their son Hugh’s new bride. His son Edward would be mooning over some wench and the rest of his children would be playing some absurd game. The king would be on his throne, taking the purely disinterested advice that Hugh could have offered him but never did.

He’d truly loved them all, and he’d brought them all to ruin. It was by far his worst sin. Why had not Trussell included that in his thunderings?

He prayed for forgiveness, perhaps audibly enough to be overheard by those surrounding him, for there was scornful laughter. Then a man in black appeared beside him. Of the faces that surrounded him, his was the only one that showed no hatred on it. It showed nothing, in fact; the man was simply following his trade. Hugh hoped he was reasonably good at it; Arundel’s executioner, as the queen’s men had delighted in informing him, had been a rank amateur who had taken twenty strokes to sever the earl’s head. He slid his rings off his fingers and handed them to his executioner. “Go to it,” he said tonelessly.

***

To separate them from the increasingly boisterous crowd, a little stand had been erected near the gallows for the queen and her son and the higher nobility. Still wearing a look of patient, slightly pained endurance, Isabella watched as Despenser, wearing nothing but his crown of nettles, was lifted aloft. Zouche, standing a few feet off with the queen’s other leaders, glanced at young Edward’s face but could read nothing in it.

After dangling in the air a short time, Hugh was lowered to a platform below the gallows, next to which a good-sized fire had been lit. For a moment, he lay still, much to the crowd’s dismay; then, after a few slaps from the executioner, he started to cough and gasp and opened his eyes. The executioner, satisfied that his charge was as awake as he was going to get, nodded to a boy who like a surgeon’s apprentice was standing nearby with several knives and an ax. The boy handed over the smallest of the knives, and the executioner bent to his work.

Despenser let out a strangled cry, and the executioner held up Hugh’s genitals. Amid the cheers and jests, Isabella’s smile was too slight to be detected as they quivered in the air. After dropping them in the fire (“Listen to ’em sizzle!” a spectator shouted happily. “Like bacon!”), the executioner took a larger knife and opened Hugh’s abdomen. Hugh moaned and turned his head back and forth, then grew quiet. He was motionless when his heart was plucked out and thrown into the fire.

The boy handed over the ax. “Behold the head of a traitor!”

The crowd shrieked with sheer joy, and men clapped each other on the backs and shoulders as if they had personally caught the king’s chamberlain and brought him to justice. As the head, which was to be sent to London, was carefully put aside, Zouche found that he could not watch Hugh’s blood-covered body being cut into four pieces. Instead, he stared at the ring on his right hand as he twirled it round and round.

Thursday, November 23, 2006

Thanksgiving Stuff

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone! I've been asked to make my specialty for dinner at my folks' house. As you can see, this will involve quite some slaving over the stove:

Actually, before you start dissing Stove Top Stuffing (which I'm afraid I prefer to most homemade stuffing--I'm so perverse), bear in mind that one of its chief inventors was a woman, Ruth Siems, who died just last year. So every forkful of Stove Top you have this Thanksgiving is, in a sense, your tribute to the strides women have made over the years.

Besides, it's damn tasty. Really.

Actually, before you start dissing Stove Top Stuffing (which I'm afraid I prefer to most homemade stuffing--I'm so perverse), bear in mind that one of its chief inventors was a woman, Ruth Siems, who died just last year. So every forkful of Stove Top you have this Thanksgiving is, in a sense, your tribute to the strides women have made over the years.

Besides, it's damn tasty. Really.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

The Reluctant Queen and the Bored Blogger

For my recent birthday, I got an Amazon gift certificate. Thrifty girl that I am, I spent most of it on used books, and my acquisitions have been rolling in gradually over the past couple of weeks.

First to arrive was a 1962 historical novel, The Reluctant Queen by Molly Costain Haycraft, about Henry VIII's sister Mary (not to be confused with The Reluctant Queen by Jean Plaidy, about Richard III's queen, Anne Neville). Haycraft, as you might know or have guessed, was the daughter of popular historian and novelist Thomas Costain.

Unfortunately, this book didn't give me much bang for my birthday buck. About two-thirds of the novel, which ends with Mary's marriage to Charles Brandon, is concerned with Mary's life before she marries the French king, and although there are a few nice scenes between Mary and her brother, the main focus--the developing love affair between Mary and Charles Brandon--just isn't that interesting. It's the usual story--the lovers get jealous of each other's admirers, have a tiff or two, realize their love, declare their love, and then are separated by mean Harry. Once Mary becomes Queen of France, the book doesn't improve much, though I had a glimpse of hope when little Anne Boleyn appeared on the scene. Unfortunately, her appearance was only a cameo one, as was Jane Seymour's. Even the lecherous Francis doesn't liven up the novel as much as he should. Charles Brandon must have been quite the charmer, but it doesn't come through here, I'm afraid. He and Mary are personable and attractive, but not much more than that, and as a result the book just never lit up for me.

I've read two other books by Haycraft, King's Daughters, about the daughters of Edward I and especially his daughter Elizabeth, and The Lady Royal, about Isabella, daughter of Edward III, and found them to be more entertaining than this one. Perhaps the difference lies in that these books dealt with relatively obscure people, and thus weren't retreading familiar ground, whereas Mary and Brandon's story has been told many times, requiring anyone who writes about them yet again to display more pizazz than was exhibited here.

All in all, a pleasant enough love story, but not something I'd recommend tracking down except for lovers of all things Tudor.

Speaking of which, I'm debating whether to buy the forthcoming Philippa Gregory novel or just to wait my turn at the library. Those who have read it seem to prefer it over her earlier novels, which I didn't really care for, so perhaps I'll take the plunge.

First to arrive was a 1962 historical novel, The Reluctant Queen by Molly Costain Haycraft, about Henry VIII's sister Mary (not to be confused with The Reluctant Queen by Jean Plaidy, about Richard III's queen, Anne Neville). Haycraft, as you might know or have guessed, was the daughter of popular historian and novelist Thomas Costain.

Unfortunately, this book didn't give me much bang for my birthday buck. About two-thirds of the novel, which ends with Mary's marriage to Charles Brandon, is concerned with Mary's life before she marries the French king, and although there are a few nice scenes between Mary and her brother, the main focus--the developing love affair between Mary and Charles Brandon--just isn't that interesting. It's the usual story--the lovers get jealous of each other's admirers, have a tiff or two, realize their love, declare their love, and then are separated by mean Harry. Once Mary becomes Queen of France, the book doesn't improve much, though I had a glimpse of hope when little Anne Boleyn appeared on the scene. Unfortunately, her appearance was only a cameo one, as was Jane Seymour's. Even the lecherous Francis doesn't liven up the novel as much as he should. Charles Brandon must have been quite the charmer, but it doesn't come through here, I'm afraid. He and Mary are personable and attractive, but not much more than that, and as a result the book just never lit up for me.

I've read two other books by Haycraft, King's Daughters, about the daughters of Edward I and especially his daughter Elizabeth, and The Lady Royal, about Isabella, daughter of Edward III, and found them to be more entertaining than this one. Perhaps the difference lies in that these books dealt with relatively obscure people, and thus weren't retreading familiar ground, whereas Mary and Brandon's story has been told many times, requiring anyone who writes about them yet again to display more pizazz than was exhibited here.

All in all, a pleasant enough love story, but not something I'd recommend tracking down except for lovers of all things Tudor.

Speaking of which, I'm debating whether to buy the forthcoming Philippa Gregory novel or just to wait my turn at the library. Those who have read it seem to prefer it over her earlier novels, which I didn't really care for, so perhaps I'll take the plunge.

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Shame, Shame!

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Buckingham's Wife, and Some Very Stylish Queens

Today I finished reading Hilda Lewis's Wife to Great Buckingham, a 1959 novel about Catherine Manners, wife to George Villiers. This is the second book by Lewis I've read, the first being Harlot Queen, about Isabella, wife to Edward II.

Harlot Queen was written in the third person, and I wish this novel had been also. Catherine is the narrator, and unfortunately, she never really came to life for me. She showed some promise in the early part of the novel, dealing with her youth, and she became almost interesting in the last chapter of the novel, dealing with her second marriage, but in the long stretch in between she was little more than a reporter of other people's doings. This could have worked, I suppose, in some circumstances, but I don't think it did here.

A big problem for me was that although Catherine often professes her love for Buckingham (and in real life, I believe she was quite fond of him, and he of her), we see very little of the two as a couple, and on the few occasions when we do, we see little of their affection in evidence. On the few occasions when the two hold a conversation, it might as well be one between business associates as one between a married couple.

Historically, this novel seems rather eccentric. As Lewis would have it, the main cause of Buckingham's undoing was his hopeless love for the Queen of France, which drives him into an unpopular war and Lewis's prose into the realm of the purple: "'His passion burns him like a fire. He starves for the sight of her. I tell you he cries out her name in his sleep.'"

Add to this a tedious subplot involving Catherine's adulterous sister-in-law and her persecution by the Villiers family, and I admit I was doing some heavy-duty skimming toward the end.

Sadly, I don't know much about the real-life Catherine Manners, but the online Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article about her by Jane Ohlmeyer indicates that she was an interesting woman, one in need of a better novel than this.

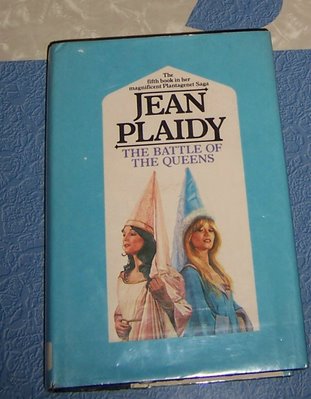

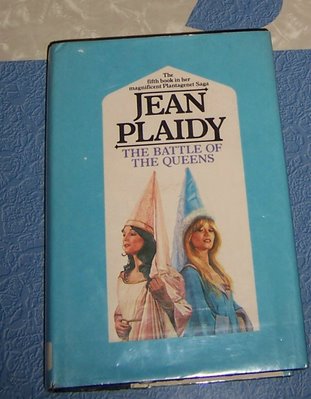

On a happier note, this is one of my finds at the book sale on Monday. Check out the nicely contrasting queens--brunette Blanche of Castile in pink, blond Isabella of Angouleme in blue. Not to mention Isabella's bangs (fringe, I think, to some of you) and the big pointy hennins that these thirteenth-century trendsetters have acquired a couple of centuries beforehand.

Harlot Queen was written in the third person, and I wish this novel had been also. Catherine is the narrator, and unfortunately, she never really came to life for me. She showed some promise in the early part of the novel, dealing with her youth, and she became almost interesting in the last chapter of the novel, dealing with her second marriage, but in the long stretch in between she was little more than a reporter of other people's doings. This could have worked, I suppose, in some circumstances, but I don't think it did here.

A big problem for me was that although Catherine often professes her love for Buckingham (and in real life, I believe she was quite fond of him, and he of her), we see very little of the two as a couple, and on the few occasions when we do, we see little of their affection in evidence. On the few occasions when the two hold a conversation, it might as well be one between business associates as one between a married couple.

Historically, this novel seems rather eccentric. As Lewis would have it, the main cause of Buckingham's undoing was his hopeless love for the Queen of France, which drives him into an unpopular war and Lewis's prose into the realm of the purple: "'His passion burns him like a fire. He starves for the sight of her. I tell you he cries out her name in his sleep.'"

Add to this a tedious subplot involving Catherine's adulterous sister-in-law and her persecution by the Villiers family, and I admit I was doing some heavy-duty skimming toward the end.

Sadly, I don't know much about the real-life Catherine Manners, but the online Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article about her by Jane Ohlmeyer indicates that she was an interesting woman, one in need of a better novel than this.

On a happier note, this is one of my finds at the book sale on Monday. Check out the nicely contrasting queens--brunette Blanche of Castile in pink, blond Isabella of Angouleme in blue. Not to mention Isabella's bangs (fringe, I think, to some of you) and the big pointy hennins that these thirteenth-century trendsetters have acquired a couple of centuries beforehand.

Monday, November 13, 2006

Cheap Books, and Lots of Them

Warning: this post contains graphic descriptions of large quantities of books at cheap prices.

I volunteered at my county library's annual book sale today and helped unbox books and arrange them on tables. Before you commend me for my civic-mindedness, remember the Big Perk here: first dibs on the books (500,000 under one roof, according to the newspaper) before they go on sale to the public.

I've been to this sale before, but always as a customer and always on the weekend, after the best books had been grabbed by the early birds. By contrast, the scene today was almost pornographic: a former discount department store lined front to back, side to side, with tables of books, many of them very lightly read. Volunteers got to grab paperbacks for 50 cents (including trade paperbacks) and hardbacks for two bucks.

I get the shivers just remembering it.

I didn't find anything truly obscure (no $700 Hale books here, I'm afraid), but I did find a lot of things on my wish list. Among others, I brought home several of Alison Weir's biographies, five Jean Plaidys, a copy of Stella Tillyard's Aristocrats that appeared never to have been read, a copy of Jane Dunn's Elizabeth and Mary that also looked pristine, and a copy of Dorothy Dunnett's King Hereafter that will probably take me years before I get around to reading it but nonetheless is adding a certain respectability to my shelf tonight.

I'm due to go back Friday, but I'm seriously tempted to go back tomorrow. (Did I mention I get to wear a sexy orange T-shirt with VOLUNTEER on it?)

It was rather funny to see what tables people gravitated to. General Fiction (including historical fiction, which, alas, does not have its own table) attracted a great many unpackers, as did the Juvenile, History, and Biography tables. When I left in the early afternoon, the Horror tables hadn't been touched yet (evidently too scary an experience). Strangely, the Romance tables also had yet to be unpacked. Maybe the romance readers showed up in the afternoon, after a morning of luxuriating in their king-size beds.

Some more thoughts:

I personally unpacked six copies of Bill Clinton's autobiography, and there were another dozen or so on the Presidents table the last time I looked. Most of them were pristine ex-library copies, suggesting that whoever decided that each branch needed multiple copies needs to reconsider the next time a President writes a book.

The books were sorted before they were sent over for unpacking. The sorters were evidently of two minds about James Frey's A Million Little Pieces. Of the dozen or so copies I noticed, half were in fiction, the other half in biography. (There wasn't a special table for Rip-Offs.) You can get a copy for 50 cents if you really want one, but this is one I'd save for Bag or Box day (Sunday), where you can get it even cheaper.

Speaking of memoirs, there were a lot of them (presumably genuine) on the Biography table. In fact, it seems that everyone in whom I'm not the least bit interested has written one.

Finally, almost every fifth book I unpacked for the Biography table had something to do with Princess Diana. This made me think either (1) there cannot possibly be anything left to say about Princess Diana or (2) I should get cracking and try to find something to say about Princess Diana.

I volunteered at my county library's annual book sale today and helped unbox books and arrange them on tables. Before you commend me for my civic-mindedness, remember the Big Perk here: first dibs on the books (500,000 under one roof, according to the newspaper) before they go on sale to the public.

I've been to this sale before, but always as a customer and always on the weekend, after the best books had been grabbed by the early birds. By contrast, the scene today was almost pornographic: a former discount department store lined front to back, side to side, with tables of books, many of them very lightly read. Volunteers got to grab paperbacks for 50 cents (including trade paperbacks) and hardbacks for two bucks.

I get the shivers just remembering it.

I didn't find anything truly obscure (no $700 Hale books here, I'm afraid), but I did find a lot of things on my wish list. Among others, I brought home several of Alison Weir's biographies, five Jean Plaidys, a copy of Stella Tillyard's Aristocrats that appeared never to have been read, a copy of Jane Dunn's Elizabeth and Mary that also looked pristine, and a copy of Dorothy Dunnett's King Hereafter that will probably take me years before I get around to reading it but nonetheless is adding a certain respectability to my shelf tonight.

I'm due to go back Friday, but I'm seriously tempted to go back tomorrow. (Did I mention I get to wear a sexy orange T-shirt with VOLUNTEER on it?)

It was rather funny to see what tables people gravitated to. General Fiction (including historical fiction, which, alas, does not have its own table) attracted a great many unpackers, as did the Juvenile, History, and Biography tables. When I left in the early afternoon, the Horror tables hadn't been touched yet (evidently too scary an experience). Strangely, the Romance tables also had yet to be unpacked. Maybe the romance readers showed up in the afternoon, after a morning of luxuriating in their king-size beds.

Some more thoughts:

I personally unpacked six copies of Bill Clinton's autobiography, and there were another dozen or so on the Presidents table the last time I looked. Most of them were pristine ex-library copies, suggesting that whoever decided that each branch needed multiple copies needs to reconsider the next time a President writes a book.

The books were sorted before they were sent over for unpacking. The sorters were evidently of two minds about James Frey's A Million Little Pieces. Of the dozen or so copies I noticed, half were in fiction, the other half in biography. (There wasn't a special table for Rip-Offs.) You can get a copy for 50 cents if you really want one, but this is one I'd save for Bag or Box day (Sunday), where you can get it even cheaper.

Speaking of memoirs, there were a lot of them (presumably genuine) on the Biography table. In fact, it seems that everyone in whom I'm not the least bit interested has written one.

Finally, almost every fifth book I unpacked for the Biography table had something to do with Princess Diana. This made me think either (1) there cannot possibly be anything left to say about Princess Diana or (2) I should get cracking and try to find something to say about Princess Diana.

Friday, November 10, 2006

Something Shady Going On Here

In my never-ending quest for seriously obscure novels about Edward II, a Google search led me to a list of historical novels that appeared to be from the early 20th century. There, I found one called In the Shadow of the Crown by a mysterious person called "Bidden."

An Amazon search revealed no book by Bidden of this name. I knew, of course, that Jean Plaidy's recently reissued historical novel by that name (about Mary Tudor) would turn up. What I wasn't expecting, however, was how many others did:

Shadow of the Crown by Craig Mills

Shadow of the Crown by Susan Bowden

Crown of Shadows (Coldfire Trilogy, Final Volume) by C. S. Friedman

The Crown and the Shadow: The Story of Françoise d'Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon by Pamela Hill

Shadow of the Crown: A Story of Malta by Ivy May Bolton

Crown of Shadows: An Anti-historical Play by Rodolfo Usigli

(Sadly, there's no description for this last entry, so I'm--appropriately enough--in the dark as to what an anti-historical play is.)

To make matters even shadier, Nicholas Carter also wrote a series called Shadow on the Crown. Not to be outdone, Ulverscroft reprinted a number of historical novels about royal figures. It called this large-print series Shadows of the Crown

So, plenty of shady characters here. But where's Bidden?

An Amazon search revealed no book by Bidden of this name. I knew, of course, that Jean Plaidy's recently reissued historical novel by that name (about Mary Tudor) would turn up. What I wasn't expecting, however, was how many others did:

Shadow of the Crown by Craig Mills

Shadow of the Crown by Susan Bowden

Crown of Shadows (Coldfire Trilogy, Final Volume) by C. S. Friedman

The Crown and the Shadow: The Story of Françoise d'Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon by Pamela Hill

Shadow of the Crown: A Story of Malta by Ivy May Bolton

Crown of Shadows: An Anti-historical Play by Rodolfo Usigli

(Sadly, there's no description for this last entry, so I'm--appropriately enough--in the dark as to what an anti-historical play is.)

To make matters even shadier, Nicholas Carter also wrote a series called Shadow on the Crown. Not to be outdone, Ulverscroft reprinted a number of historical novels about royal figures. It called this large-print series Shadows of the Crown

So, plenty of shady characters here. But where's Bidden?

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

Wacky Wednesday

We had a lot of fun in our house last night with Romance by You, a site that lets you create a personalized romance novel by inputting answers into various categories (name of heroine, hair color, name of hero, etc.). To get an entire book, you have to pay (personally, I think it's a clever gift idea), but you can generate some sample excerpts online. I especially enjoyed the Medieval Passion book, which allows customers to enter their pet's name as well as those of human characters. Naturally, I entered Boswell's name, and the resulting excerpt, where Boswell showed a great interest in pork rinds and napping, caught his personality uncannily well, I thought. (My daughter put in Tim Gunn and Heidi Klum of "Project Runway" as her hero and heroine, which generated plenty of giggles at home.)

Moving on to a totally unrelated topic, this quiz answered one of those questions that has always puzzled me:

As I'm a subway aficionado, I was quite pleased with these results. The New York subway would have suited me fine also.

Moving on to a totally unrelated topic, this quiz answered one of those questions that has always puzzled me:

You're the London Underground!

Once the benchmark for the industry you work in, now you've

been through a very difficult experience. This has made people less likely

to spend time with you and even afraid of you in some cases. In future, it

might be best to not respond to your own fear with threats of shootings.

Regardless, you remain a staple in your community and even a new symbol of

hope. You may soon be as popular as the Fire Department of New

York.

Take the Trains and Railroads Quiz

at RMI Miniature Railroads.

As I'm a subway aficionado, I was quite pleased with these results. The New York subway would have suited me fine also.

Monday, November 06, 2006

Living in a Barbie World

Today I got a card from eBay thanking me for seven years of doing business with it, which reminded me of my first eBay purchase: Francie, Barbie's Mod cousin, issued in the mid-1960's. This happened around my 40th birthday, an event that in my mother's case inspired her to dye her hair blond and acquire a canary. I'd look pretty silly as a blonde, and a canary wouldn't last long around our four cats, so I ended up going on eBay and acquiring one of my favorite childhood dolls, which led to more acquisitions. Here's Francie on the left with Barbie in the center and Stacey (Barbie's British friend)on the right:

I don't buy many Barbies these days, but before I eased up I had succeeded in replacing many of my childhood dolls, all of which had been stolen from my parents' house years ago. (Barbie thieves, there's a little pink circle in hell meant especially for you.) I bought new Barbies too, including this Barbie and Midge, who feature on my website redressed in other Barbie clothes as two of my characters, Queen Isabella and Eleanor de Clare. (Isabella's the blond Barbie, Eleanor the redheaded Midge.)

So what does this have to do with historical fiction, you might ask? Only this: I credit Barbie with my development as a writer, for long before I could write stories on paper, I was enacting them using Barbie and her friends, who became characters in an ongoing drama that lasted well into my 11th year. As my female dolls greatly outnumbered my male dolls, this occasionally affected my storylines--but just as with historical fiction you have to work within the known facts, with the Barbie world, you have to work within there being only so many Kens to go around.

I don't buy many Barbies these days, but before I eased up I had succeeded in replacing many of my childhood dolls, all of which had been stolen from my parents' house years ago. (Barbie thieves, there's a little pink circle in hell meant especially for you.) I bought new Barbies too, including this Barbie and Midge, who feature on my website redressed in other Barbie clothes as two of my characters, Queen Isabella and Eleanor de Clare. (Isabella's the blond Barbie, Eleanor the redheaded Midge.)

So what does this have to do with historical fiction, you might ask? Only this: I credit Barbie with my development as a writer, for long before I could write stories on paper, I was enacting them using Barbie and her friends, who became characters in an ongoing drama that lasted well into my 11th year. As my female dolls greatly outnumbered my male dolls, this occasionally affected my storylines--but just as with historical fiction you have to work within the known facts, with the Barbie world, you have to work within there being only so many Kens to go around.

Thursday, November 02, 2006

A Very Brief Appreciation of William Styron, and Another Jane Lane

I was sorry to read last night that William Styron had died. I have to admit that I found his Lie Down in Darkness a bit overwrought, and I can't remember if I ever read The Confessions of Nat Turner, but I thought Sophie's Choice was a wonderful novel, with one of the best closing lines I've ever read: "This was not judgment day--only morning. Morning: excellent and fair."

I was fortunate enough to see William Styron speak at my college many years ago. He spoke a little bit about himself, saying that he was "not glib," and he read a very funny chapter from Sophie's Choice, where the callow hero Stingo, going to date a Jewish girl for the first time, is much taken aback to find that her father is a worldly art collector instead of the pious, insular Old World figure Stingo had expected. Indeed, perhaps one of the best achievements of Sophie's Choice is the ease with which the tragedy of Sophie is blended with Stingo's often comic misadventures. (The earliest pages, where Stingo describes his job as a slush-pile reader for a publisher, are among the funniest I've ever read.)

So, a morning toast to the memory of William Styron.

On another note, I finished reading The Young and Lonely King, a 1969 historical novel by Jane Lane, last week. Just a word in case anyone decides to reissue this novel; it may have one of the worst titles I've ever seen. Not only does it lack shelf appeal ("Wow! A novel about a young king! And he's lonely!"), it also is the sort of title that likely will lead anyone seeing it in a reader's hand to conclude that the reader isn't a barrel of fun either. (Passenger on airplane seeing fellow passenger holding The Young and Lonely King: "Well, at least she probably won't talk throughout the whole flight.")

Title aside, I enjoyed this novel about Charles I. Unlike The Severed Crown, which was told by multiple narrators, this is a third-person narration that begins with Charles I's childhood and ends at a high point in his life; the birth of a son to Henrietta Maria. Not action-packed, it's essentially a story of Charles's developing character and centers around his relationships: with his parents, his siblings, his friend Buckingham, and finally with his temperamental wife. Lane has a sardonic, yet compassionate narrative voice and a sharp eye for character; James I is especially memorable. There's even a rather sweet love story here: that between Charles I and Henrietta Maria, who start their marriage as an ill-matched pair and eventually fall deeply in love with each other. The scene where Henrietta Maria goes to comfort her husband after the death of Buckingham and says her first English words to him is especially good--moving, but not mawkish.

All in all, a book that whet my appetite for more Jane Lane.

By the way, you'll notice a new poll in the sidebar. Did Richard III kill the little princes, or did someone else do the deed? Or were they not killed at all? You decide.

I was fortunate enough to see William Styron speak at my college many years ago. He spoke a little bit about himself, saying that he was "not glib," and he read a very funny chapter from Sophie's Choice, where the callow hero Stingo, going to date a Jewish girl for the first time, is much taken aback to find that her father is a worldly art collector instead of the pious, insular Old World figure Stingo had expected. Indeed, perhaps one of the best achievements of Sophie's Choice is the ease with which the tragedy of Sophie is blended with Stingo's often comic misadventures. (The earliest pages, where Stingo describes his job as a slush-pile reader for a publisher, are among the funniest I've ever read.)

So, a morning toast to the memory of William Styron.

On another note, I finished reading The Young and Lonely King, a 1969 historical novel by Jane Lane, last week. Just a word in case anyone decides to reissue this novel; it may have one of the worst titles I've ever seen. Not only does it lack shelf appeal ("Wow! A novel about a young king! And he's lonely!"), it also is the sort of title that likely will lead anyone seeing it in a reader's hand to conclude that the reader isn't a barrel of fun either. (Passenger on airplane seeing fellow passenger holding The Young and Lonely King: "Well, at least she probably won't talk throughout the whole flight.")

Title aside, I enjoyed this novel about Charles I. Unlike The Severed Crown, which was told by multiple narrators, this is a third-person narration that begins with Charles I's childhood and ends at a high point in his life; the birth of a son to Henrietta Maria. Not action-packed, it's essentially a story of Charles's developing character and centers around his relationships: with his parents, his siblings, his friend Buckingham, and finally with his temperamental wife. Lane has a sardonic, yet compassionate narrative voice and a sharp eye for character; James I is especially memorable. There's even a rather sweet love story here: that between Charles I and Henrietta Maria, who start their marriage as an ill-matched pair and eventually fall deeply in love with each other. The scene where Henrietta Maria goes to comfort her husband after the death of Buckingham and says her first English words to him is especially good--moving, but not mawkish.

All in all, a book that whet my appetite for more Jane Lane.

By the way, you'll notice a new poll in the sidebar. Did Richard III kill the little princes, or did someone else do the deed? Or were they not killed at all? You decide.

Subscribe to: